Aground and Off Again

|

John Ellsworth explains how to avoid running aground and

what to do when the inevitable occurs and the bottom comes up.

|

|

First appeared in SAIL magazine • All rights reserved • © 2006 John Ellsworth

|

Ask any experienced sailor, and he or she will admit to having run aground at some point. It's part of sailing. Unless you are landing a centerboard boat on the beach, however, running aground is an experience you try to avoid. By knowing your position and the depth of the water, you can prevent a surprise meeting with the bottom. And by knowing what to do if you should happen to run aground, you can get off quickly and get back to sailing.

Know your position. Always sail in a manner that reduces the chance of running aground. If you are sailing in unfamiliar waters, study the charts. Check the height of the tide. When does it turn? How much does it rise and fall?

When you are not sure, check the depth with a leadline or depthsounder. Sail into questionable waters as the tide is rising; then if you do run aground, you'll float off in short time. When passing through channels or inlets, stay on the windward side. If you hit bottom, the wind will help push you toward deeper water in the center of the channel.

If you are anchoring, check the depth within the full circumference of your swing on the anchor line. Use your dinghy and a leadline, if necessary. Be sure to figure in the height of the tide to ensure that there will be enough water during your stay.

Knowing your position and the depth of the water below you at all times reduces the odds of running aground but doesn't eliminate them. To be ready for a grounding, you should develop a plan of action for getting free.

Your plan will depend on several variables, among them the boat type, the nature of the bottom, wind and current direction, wave conditions, your distance from shore, the number of crew aboard, and whether you have a dinghy. Although you must consider these variables in each situation, three principles of action remain the same:

- Stabilize your boat: If you hit the bottom, immediately release force on the boat by freeing your sheets to luff the sails. Depending on the situation, you may then need to drop the sails and set an anchor.

- Reduce your draft: Raise the centerboard if you have one, or heel the boat to reduce draft. If you are hard aground, remove crew weight and heavy gear to lighten up.

- Sail off in the opposite direction: Turn around and sail off the bottom by retracing the course that brought you aground. This ensures that you will move back into deeper water and not onto the bottom again. Always try to turn the boat so that you are sailing off bow first.

Centerboard boats. Running aground in a centerboard boat is rarely a problem. Because smaller centerboarders need very little depth, you can usually see the bottom and avoid shallow water. The draft of a centerboard boat can be quickly reduced by simply raising the board. If you do bump against the bottom, you can pull the board up partway, then turn around and sail back into deeper water.

When the wind is pushing the boat onto a shoal, you may not be able to turn around and sail free. If you run aground while going downwind and cannot make any distance to windward with your board up, luff the sails to stabilize the boat. Then have one or more crewmembers jump out and push the boat toward deeper water until you can lower the board enough to sail.

Make sure that those going into the water are wearing life jackets and shoes. Rig a tether they can hold, and take any other necessary safety precautions. If conditions are rough or the water is very cold, it may be best to stay in the boat, set an anchor if you have one, and ask a passing boat for a tow.

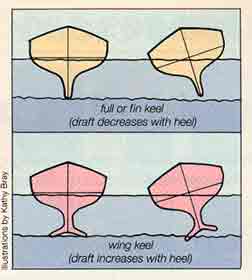

Keelboats. If you are sailing a keelboat, the keel type affects your plan for getting off the bottom. Conventional keels are deepest when the boat is upright, while wing keels are deepest when heeled (Fig. 1). The key to reducing draft with a conventional keel is to heel the boat. The following strategies for getting off the bottom apply to boats with conventional keels.

|

Figure 1. Understand how the draft of your keel changes after you release the sheets and the boat stands upright. the draft of a fin or full keel is maximized, while a wing keel requires less depth when vertical. |

Stabilize. If you hit the bottom while sailing, free the sheets and unload pressure on the sails. The boat will stand upright and stop.

Reduce draft. You can often use your crew's weight to reduce draft. On a small keelboat, simply move everyone to one side. On a larger boat, you may need a bit more leverage. Drop the main, then get a crewmember or two on the boom and swing it out to. As the boat heels and draft decreases, swing the bow around by trimming or backing the jib. Make sure that you don't drive the boat farther aground as you turn.

Move off in the opposite direction. After reducing draft, try to pivot the boat so that you will leave the shallows bow first. If you cannot turn around but have an engine, you can use the reverse gear to back off. Be sure that your rudder is clear of the bottom before backing down, and move slowly to avoid pulling churned bottom sediment through your cooling-water intake.

If you are unable to free the boat on the first or second attempt, you must either apply more force to move your boat off the bottom, reduce your draft further, or both. Among the options for moving your boat into deeper water are to kedge with an anchor or to request a tow from another boat.

Use an anchor to kedge. Kedging involves hauling on the line of an anchor set in deeper water to move the boat out of the shallows. If the water is very shallow and you've got a light anchor, you may be able to heave the anchor far enough from the boat to set it firmly for kedging. Otherwise, use a dinghy or another boat to set the anchor in deep water. Again, try to pivot the boat around using the anchor or sails so that you are hauling out bow first.

Once the anchor is set and the boat is turned around, lead the anchor line through the bow chock and around a winch. Now crank it in. If cranking is difficult, lead the tail around a second winch and have two crewmembers work simultaneously. Be sure your lead is clean, and synchronize your efforts with the rise and fall of waves or wakes. If you have effectively reduced your draft, kedging will often get you free.

Ask another boat for a tow. If kedging is not effective or not possible and another boat with an engine is available, towing is your next option. Before securing the towline, use hand signals or a VHF to agree on a plan with the towing skipper. Towing will apply much force to the lines, so do not use cleats. Make your towline fast around the mast with a bowline, and remember to use chafing gear. Lead the towline forward through the bow chock, bring it outside, up, and over the pulpit, and coil it for heaving.

|

Be sure to stay clear of the towline—a backlash could cause serious injuries

|

The towing skipper should back down toward you until the boats are close enough for heaving (30 to 50 feet apart). Once the line is secured on the towing boat, the towing skipper should shift into forward and work to pivot your bow around if you have not been able to do so. Once you are headed for deep water, the towing skipper can apply more power and pull you free.

Because the boats must maneuver near one another, use caution when towing in rough conditions. Be sure to stay clear of the towline in case it parts under the strain-a backlash could cause serious injuries.

Kedging and towing are easier when combined with methods for reducing your draft. As described earlier, shifting crew weight to one side of the boat or getting one or two crewmembers out on the boom and swinging it out over the water should do the trick. If not, here are some other things you can do.

Lighten up. If you are really stuck, got crewmembers and heavy gear such as sails, fuel tanks, outboard motor, and spare anchors off the boat and into a dinghy or assisting boat. If necessary, empty your water tanks.

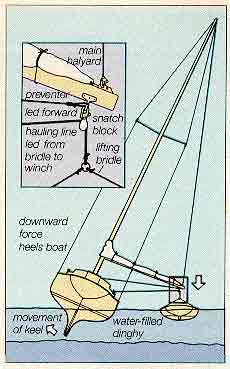

Use a water-filled dinghy. If short of crew, rig a lifting bridle to your dinghy and then fill it with water (Fig. 2). This method pulls the end of the boom and tip of the mast toward the heavy dinghy, heeling the boat and reducing draft.

|

Figure 2. The water-filled dinghy will provide extra leverage for inducing heel and reducing draft. Fasten the main halyard to the outhaul car at each end of the boom, attach a snatch block, and run a preventer forward. Lead a line from the lifting bridle through the snatch block to a winch. Cleat the main halyard with the boom 15 to 20 degrees above horizontal. Slowly winch in the dinghy line to heel the boat over in the water. |

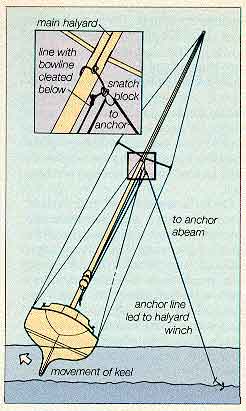

Haul an anchor line aloft. In this method, the line from an anchor is set directly off one side of the boat, or abeam, and is raised aloft and then tensioned to pull the mast horizontally and heel the boat. Naturally, the higher the line is led, the greater the advantage (Fig. 3).

|

Figure 3. Leading an anchor line aloft is another way to heel the boat and reduce draft. The anchor must be set perpendicular to the direction of the boat, or abeam, so that the mast is pulled laterally as the anchor line is tensioned on a winch and draft is reduced. |

Take a piece of line longer than the distance from the deck to the first spreaders. Tie a bowline around the mast with a loop about twice the diameter of the spar, and attach to it a halyard shackle and a snatch block.

Lead the anchor line through the snatch block to a halyard winch. Hoist the halyard to raise the bowline and snatch block to a few feet below the first spreaders, then cleat the halyard and secure the bowline.

Now crank in the anchor line to heel the boat as you apply force with the engine, kedge, or towline. Once you have broken free, retrieve your anchor, using a dinghy if it is in shoal water.

Stay calm and follow your plan. Groundings do occur, even among the most experienced sailors. So if one day you hear a thump and your boat comes to a halt, remember that you have many options for getting off again. The important thing is to act quickly and confidently, using a well thought-out plan.

|

Aground with a wing keel

A wing keel puts two factors in your favor when sailing in unfamiliar waters. Because wing keels draw less water than conventional keels, you will be less apt to run aground in the first place. second, because the wing keel's draft is deeper when the boat is heeled, if you feel the boat hit bottom, release the sheets immediately. When the boat slows and stands upright, the draft is reduced and you can move into deeper water.

If you do bury a wing keel in the mud, try this procedure devised by the engineers from Pearson Yachts, who intentionally ran a wing-keeled Pearson 31 into the mud at 7 knots. They backed down while rapidly shifting the rudder back and forth between 60 debrees of arc. The motion rocked the boat, broke the suction between the wings and mud, and they were free in a short time.

If this technique doesn't work on the first attempt, lighten the boat by removing heavy gear. While backing down and turning the rudder from side to side, try to rock the boat by shifting crew weight for and aft. This can also help break the suction.

|

|

|

|