Sailing Comes Inch by Inch

|

There's no need to make dramatic changes.

A little move goes a long way, says John Ellsworth.

|

|

First appeared in SAIL magazine • All rights reserved • © 2006 John Ellsworth

|

Sailing is one sport in which you do practically everything by inches. Small adjustments in steering, sail trim, and boathandling in response to variations in wind and water are the mark of an experienced sailor. When you are learning to sail, your tendency may be to overdo these adjustments-to oversteer or overtrim-and you'll sail inefficiently as a result of the drag that large movements of rudder or sail create.

You can learn from the elements themselves; wind and water share similar properties in that they customarily change direction, force, or speed gradually. When you detect a change in either element, you should mimic that change, adjusting gradually, incrementally, so that the boat interacts with the environment instead of fighting it. Monitor the elements. When the environment changes, as reflected by heel angle, helm pressure, sail shape, or wake pattern, respond with fine adjustments. With each adjustment, check your boat's response. Let your boat answer before the next adjustment.

Steering

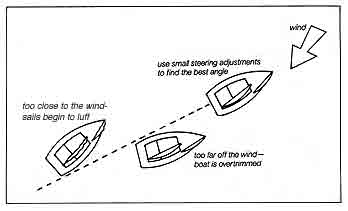

The importance of subtle steering comes into play when you are closehauled and you want to make sure you are pointing as high as you can without pinching. Let's say you are pointing efficiently while you maintain a heading on the edge of the wind. Because the wind may shift slightly, you should constantly use the helm to test whether you are at the optimum sailing angle. Try heading up in the smallest increments possible until the headsail luffs, then fall off in the same manner until it stops luffing (Fig. 1). You will be pointing as high as possible with maximum speed.

Steering in a following sea creates problems for new sailors because the helm is likely to be neutral-that is, having equal pressure port and starboard. To steer efficiently, you must apply equal pressure port and starboard with the helm. A following sea will lift the transom and cause you to yaw, or deviate from your chosen course. You may be tempted to counter this motion with dramatic tiller or wheel motion. If you pay attention you'll notice a change of pressure on the rudder as the boat begins to heel slightly with the waves. Set your eye on a landmark dead ahead, try to anticipate the approaching sea, and counter its effects with very slight helm adjustments in the direction of your course. Eventually you will find the rhythm . Once your steering is in cadence with the swells, your course will be straighter and safer.

|

Respond to any changes

in conditions with

small adjustments

|

Changing course also demands incremental steering. When you want to head up or down to a new heading near your current one, make a small change in the rudder angle, hold for a moment, return the helm amidships, and gauge how many degrees the bow swings. Continue the process of "walking" your craft to its new heading. Even if your new heading is at a wide angle, hold the slight rudder angle as you watch the compass card rotate. With 10 or 15 degrees to go, position the rudder amidships and then proceed with the walking maneuver until you arrive at your new heading.

In both cases, you should be able to achieve your new heading with precision. With too much rudder movement, the boat may swing beyond the new course, and you'll need to move the rudder in the opposite direction to correct it, The idea is to reduce drag by minimizing the rudder movement needed to control the heading (Fig. 1).

|

| Figure 1. When sailing upwind, steer with small movements of the rudder to find your most efficeint angle. Turn the boat toward the wind until the sails luff slightly, then head off. When the boat slows down and feels over-trimmed, turn back toward the wind. Work to minimize the changes in your heading. |

Maneuvering

Incremental actions are also important when you maneuver the boat by tacking and gybing. Your tacking maneuver can benefit from the incremental approach in regard to your commands and trimming to match acceleration after the tack.

The typical command sequence for coming about should be done in steps, with the appropriate action taken as a consequence of the commands. Don't surprise your crew with sudden requests. Abrupt commands create drag on crew performance. You should let your crew know what to expect by easing them into the change. Initially tell them, "We're going to tack in about 50 yards," so that they'll be mentally prepared. Then the event should progress gradually with the commands: "Prepare to come about" and "Ready to come about; hard a'lee."

Trimming the sheets for the new course can be done incrementally by loading the "new" winch during the maneuver. At "prepare to come about," your crew places one or two turns on the new winch. After "hard a1ee," directly after which the bow crosses the wind, haul in the now active sheet hand over hand. When nearly all slack is in, put an additional turn on the winch and continue hauling. Use the winch handle when you can no longer haul by hand. The wind will dictate the number of turns. The lighter the wind, the fewer turns are required. By trimming the sheets incrementally, you avoid overwrapping the winch at the outset, when the winch is freely spinning as the sheet is hauled in. A winch with too many wraps produces an override, or jammed sheet, which is very difficult to undo. Basically the same incremental technique is used when gybing -prepare the crew in advance, synchronize the actions with the commands, and trim for the new course with little bites.

|

Boat and crew should create an

accord with wind, water, and skills

|

Sail trim and balance

After a tack, use incremental adjustments in sail trim and steering to build up speed (Fig. 2). As you move out of the tack onto the new course, don't trim the sails immediately, but bring the boat up just below the best upwind angle. Then as the boat accelerates, steer closer to the wind and trim gradually.

|

|

| Figure 2. Use incremental adjustments in sail trim and steering to build up speed after a tack. As you fall into the new tack, don't trim the sails immediately and try to steer as close to the wind as possible. Turn slightly past your best upwind sailing angle and trim the sails loosely. As the boat accelerates, head up and trim in the sails gradually. |

The mainsail plays a part in accelerating; adjusting it is also done in increments. In light air, the luff and leech should be loose; the draft is around the center, and the sail is full. When a puff hits, the draft will move aft, where it doesn't belong. You need to tension the luff (with the cunningham or halyard) and trim the mainsheet. Do so a little at a time, synchronizing the acceleration, moving the draft forward, and flattening the sail. As the puff diminishes, ease the leech and luff in synchronization with the airflow. If your mainsheet has a traveler, it can help you point if you position it to windward of the centerline so that your boom is centered and low. It can also be used to reduce heeling and weather helm by creating twist in the upper part of the sail and spilling air. In both cases, the traveler should be used incrementally Make the changes in the traveler position bit by bit, and monitor the boat's performance after each change.

Proper balance is also achieved in small steps. If there is too much weather helm or heeling, you can trim the sails or shift crew weight until the boat seems balanced. Make one move at a time, and monitor the performance. On a small boat especially, crew weight, even the movement of the upper torso, can have a strong effect, as will small changes in centerboard position.

Incremental sailing is useful not only for boat performance, but also in other areas. When you are looking for another craft or a navigational aid on the horizon, instead of looking in the general direction of the mark, scan the horizon in 10- to 15-degree increments, always overlapping the last increment. The likelihood of finding the mark will increase dramatically.

There's no doubt that you will discover the importance of incremental changes in other areas. Use gradual adjustments to make your sailing more efficient, and you will create an accord between your boat, your crew, the wind, and the water.

|

|

|