My Visit with the Gypsies of Northern Spain

| In autumn of 1970, I visited the village of Infiesto, the hometown of my sister-in-law, Gloria. I took along a 35mm rangefinder Agfa camera that I borrowed from my sister.

The following entries tell the story of my encounter with the Gypsies (or “Gitanos”) of Northern Spain:

|

|

Infiesto

Mercado

The Gypsy Camp

La Chata of Astúrias

Gypsy Dancers

La Chata and her Family

River Laundry

Acceptance

Further Comments on the Gypsies

Gypsy Stories from Gloria

|

| Infiesto |

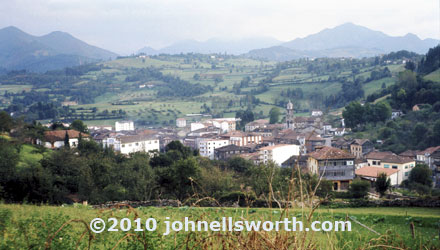

For five or six days, it had been raining steadily. I was staying in a small village in northern Spain, called Infiesto, with about 2000 inhabitants. It is the hometown of my sister-in-law, Gloria, who invited me to visit after I attended my brother’s wedding during the summer of 1969. Gloria’s mother, Mamá, welcomed me during the autumn of 1970.

My bedroom belonged to Juan Ramón, Gloria’s younger brother. He was away at college. Outside my window was a small balcony overlooking Río Piloña, a small river that wound its way about 40 kilometers northward to Mar Cantábrico. On the other side of the river were the village main streets. Infiesto, in the province of Astúrias, is settled in a valley. The climate is considered maritime, similar to that of northwestern United States. It stays green and lush all year, but it is damp and overcast, especially in the fall.

Keeping me company during my stay was Gloria’s sister, Mercedes–a cheerful, sprite, pretty señorita, who was always willing to share a meal with me, venture to a local mountain top, city, or fishing village. As often as not, her sister, Campe, would also keep us company.

|

| Mercado |

One Monday, Mercedes and I visited the mercado—or market. It was my second visit to this semi-festival event. While poking around the market amidst the cacophony of smells and colors, a hearty, dark-haired woman adorned in many layers of clothing approached me and said: “¿Da me un poco de pan?” I said to Mercedes, “What is she saying?”

“She wants a piece of bread, or any thing you are willing to give her, John. She is a Gypsy.”

She asked again–this time revealing an infant beneath her layers of clothing. The Gypsy woman’s dark eyes traced a glance from the child to me. Accompanying her engaging look, she echoed, “¿Da me un poco de pan?”

After I reached into my pocket and gave her 25 pesetas, I was chided by Mercedes for giving her too much! Mercedes told me that she picked on me because she knew I was a stranger. I stood out with my blonde hair. I was one of very few non-Spaniards in the town.

The lady was quite grateful, however, saying “grácias” three or four times. “De nada, de nada,” I exclaimed.

|

| The Gypsy Camp |

For the better part of the following week, it was chilly and raining. I spent much of my time writing letters, playing a guitar, and reading by a coal-burning stove. Occasionally we went to town, but we did not venture far.

One afternoon later in the week, the skies cleared and a shaft of sunlight shone through a western window, illuminating my hand while I was writing a letter. The warmth and brightness was welcome and prompted me to venture outside. I went for a walk up a meandering trail that started near the house. It went upward into the surroundings hills and mountains. After walking on a beaten trail for about half an hour, I heard twigs cracking, the rustling of foliage, and the word, “Marcha!” shouted with authority.

Three silhouettes emerged from the woods into a clearing, bound to cross the path. As they cleared the woods, I saw what appeared as three Gypsy boys, maybe 11-13 years old, each on a burro, each holding a stick, waddling their way across the trail. They stopped and stared at me. I stopped and smiled. The first boy remarked, “¿Una peseta, señor?”

I reached into my pocket and produced three American pennies. The boys were thrilled. They then told me they recognized me from town and wanted to know if I wanted to visit their camp. I said yes. The first boy dismounted and walked with me and the two mounted boys until we came to their autumn home, a camp across the road from Rio Piloña, about a kilometer upstream from the village.

As I entered the camp, a small contingent of Gypsy children hovered around me and started pulling on me. A woman emerged from behind a Gypsy cart and started swooshing the children away, exclaiming, “No, No.” She approached me and I immediately recognized her as being the woman to whom I gave the 25 pesetas in the mercado earlier in the week.

I am not very fluent in Spanish, but I was able to ask if I could take photos of them in their camp. They said Sunday would be good—they would dress up. I promised them I would process the film after taking the photos and give them copies of the best shots.

|

| La Chata of Astúrias |

On Sunday, I returned with Mercedes who helped translate.

I spent an hour photographing the children, the carts, the older woman and one man weaving a basket. The lady soon became known to me as La Chata. I became El Rubio.

I had the two rolls of black and white film processed and returned to the camp at mid-week. Most of the shots were simple portraits. I gave the Gypsies 10-15 prints. They were enthralled. I don’t believe they had ever seen themselves in a photograph. I asked if I could come back and take more photos. I returned at least two more times, again on a Sunday, then mid-week.

|

| Gypsy Dancers |

On Sunday, the girls were dressed up and performed a short Flamenco dance. The children participated. I got a few shots.

|

| La Chata and her Family |

As I entered the camp on my next visit, a man was weaving a basket alongside La Chata, her little daughter and her infant snuggled within the blankets.

|

| River Laundry |

The girls were washing clothes in the river where I joined them and washed my bandana.

When I went back to the campsite, the man weaving the basket looked at me with scorn. I could not figure out why he was so unfriendly. Mercedes claimed that men do not do laundry. I was breaking rules.

|

| Acceptance |

Overall, I found this group of Gypsies to be warm and accepting. When I got back to Mamá’s house, Pilár, the housekeeper, asked me, “John, what are you doing with the Gypsies?” That’s when I found out that most people disregarded them and avoided them when possible. I did not know any better, being the stranger I was.

“I like them. They happen to welcome me into their camp. They let me photograph them. They accepted me, probably because I accepted them.”

During my travels in northern Spain, occasionally I would observe Gypsies on the move, their carts being drawn by burros, trailed by a dog on a leash lashed to the cart axle. Mercedes told me the Gypsies follow the férias, or festivals, that proliferate Spain during the year. It just so happened that the férias were occurring in Astúrias during the fall I visited. According to Mercedes, they camp near villages hosting férias because it is a time for celebration and joy. In such moods, villagers are more apt to give “un poco de pan” when asked by a dark-eyed wanderer.

|

| Further Comments on the Gypsies |

As years went by, I looked more carefully at my photos and started to make more inquiries and some discoveries. I noticed the young boys I photographed had sort of a startled look on their faces. They also had stances I had seen before, in American Western films. This was the 70s. America had been importing its media to Europe for some time. I understood that the young boys were prone to sneak into movie theatres where they viewed many American westerns produced in the 50s and 60s.

So, what was I seeing in my photos? A camera is very much like a gun. You crouch if you want to lower your eye level (or make yourself a smaller target), you aim it, you shoot it, and you reload it. Is it possible the boys were reacting to a scene out of “Gunfight at OK Corral?” Or just protecting their little damsel in distress?

Something else I noticed–the woman in the cave opening with the blanket “door.” She was referred to as “Abuelita,” and was revered in the camp. She had the highest perch in the camp.

The Gypsies I visited camped close to the river bank. Mercedes told me they usually camped downstream from a town. During earlier days, townsfolk would discard useless items into the river. The current would take the items past the camp making anything easily retrieved. Early each morning, men from the camp would put empty bags or baskets on their burros and set out along the river bank, looking under rocks, between forked branches, and along the shore for “useful” items.

|

| Gypsy Stories from Gloria |

Gloria told me a couple of stories she remembers from her growing up in Infiesto. One winter, a coal truck overturned near an intersection alongside the river. Workers from the coal company scoured the road and riverbank to retrieve all the coal. The day after, three or four Gypsy children pulling an old red wagon showed up and retrieved the coal the workers had overlooked. The wagon was filled and the Gypsies had fuel for heat or cooking for a few more days.

Another story Gloria told was that of a Gypsy teenage boy who was apparently tired of living constantly by his wits. He got a job as a street cleaner. Early in the morning of his first day at work, while cleaning the street directly below Gloria’s balcony, a band of fellow Gypsies formed a circle around him, clapped in unison, and chanted, “¡Tu eres un Payo! (You are a non-Gypsy!)” Within minutes, he threw down his broom and walked away with the Gypsies. Such was the power of his reference group!

Seven years after my encounter with the Gypsies, my brother and Gloria visited Gloria’s hometown. They came upon a Gypsy cart in the market area. Pinned on the open back door of the cart was the black and white photo of “La Chata” I had taken years before.

|

|

|